When the Civil War broke out in 1861, all hands were on deck to support the war effort on both the Union and Confederate sides. Men volunteered their services to each side, leaving their families behind to fight. Women were quick to volunteer their services as well, supporting the war effort in various ways. On the home front, they worked to maintain their properties and supply the armies with the needed goods. Some women even volunteered for jobs on the front lines, serving as nurses, spies, cooks, seamstresses, and laundresses. At the time, there were strict societal expectations regarding a woman’s place; women were confined to the domestic sphere and were often seen as submissive, frail, and passive. Both the Union and Confederate armies forbade the enlistment of women, yet some women were not content to stay home and be passive. These women heroically disguised themselves as men to enlist in both the Union and Confederate armies as soldiers.

It is estimated that between 400 and 1,000 women served as soldiers during the American Civil War. However, this number is likely much higher, as not every female soldier had her identity revealed. When examining their motivations for enlistment, these women’s reasons were not so different from those of male recruits. They did not disguise themselves out of necessity but because they wanted to. Some women viewed enlistment as exciting and adventurous, yearning to leave their mundane home lives behind. Others enlisted to stay close to their loved ones, choosing to fight alongside their husbands, sons, brothers, and other male relatives. For some women, the financial gain associated with enlistment was appealing; many who enlisted came from working-class or impoverished families, and the bounties of war and paychecks would have been enticing. Pure patriotism also motivated many women’s decisions, while others simply preferred to be in action rather than stay home in despair.

Enlisting would have been easier for these women than one might imagine. They assumed masculine names, bound their breasts, padded their pants, donned ill-fitting layered clothing, and cut their hair short. At the time, the Union Army had an enlistment cutoff age 18, and the Confederate Army did not establish an age requirement. However, due to the urgent need to fill regiments with soldiers, this rule was often relaxed, and many underage boys enlisted. The disguised women blended in well with the young boys, who lacked facial hair and deep voices. Neither side standardized medical exams; those conducting the exams rarely required recruits to strip or asked for official identification. Victorian practices further helped women conceal their identities; it was standard for soldiers to sleep in their clothes, bathe in their underwear while separated from each other, and go as long as six weeks without changing their undergarments.

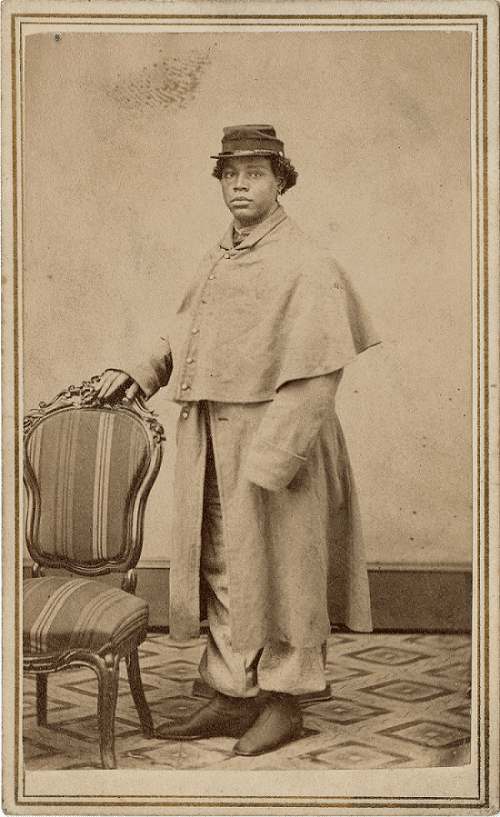

Unidentified African American Woman Soldier

Moreover, most combatants were “citizen soldiers” with no previous military training, so they all began their training together. Once in the army ranks, women learned how to act and speak like men. Evidence also suggests these female soldiers mostly kept to themselves, further concealing their identities.

While in the army, these women did everything the men did during wartime. They worked as scouts, spies, prison guards, cooks, nurses, and even engaged in combat. They were fully aware of the risks associated with their decisions. They faced injuries, imprisonment, and even death in battle. Women soldiers were known to have fought in significant battles such as Antietam, Bull Run, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Shiloh, and Vicksburg. These women were typically not discovered until they sustained serious injuries necessitating hospital care. Some were found out after a few months, while others managed to keep their identities hidden throughout the entire war. Some women’s identities remained unknown until they were killed on the battlefield. Once discovered, some women were discharged, others were imprisoned, and some were institutionalized. Interestingly, there was no evidence of any significant uproar following these discoveries; finding a woman in the army often provided a much-needed dose of humor for the soldiers.

Disguised as a man (left), Frances Clayton served many months in Missouri artillery and cavalry units. (By courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library)

While the existence of these women soldiers may have been a secret from War Department officials, evidence suggests that their presence was not unknown to the public during the war. They were written about in newspapers and obituaries. However, the press seemed less concerned with the women’s heroic actions in battle and more intrigued by the novelty of women in combat. Within the army, both sides attempted to deny the existence of female soldiers despite evidence to the contrary. After the war, some of these women returned to their lives as women, while others chose to maintain the male identities they had adopted and live as male citizens.

Unfortunately, Civil War historians largely ignore these women’s heroic acts, with textbooks rarely mentioning them. While their service did not affect the war’s outcome or significantly impact either side, their actions forever changed the public’s perception of women’s capabilities and advanced the call for gender equality.

Written By: Danielle Shults